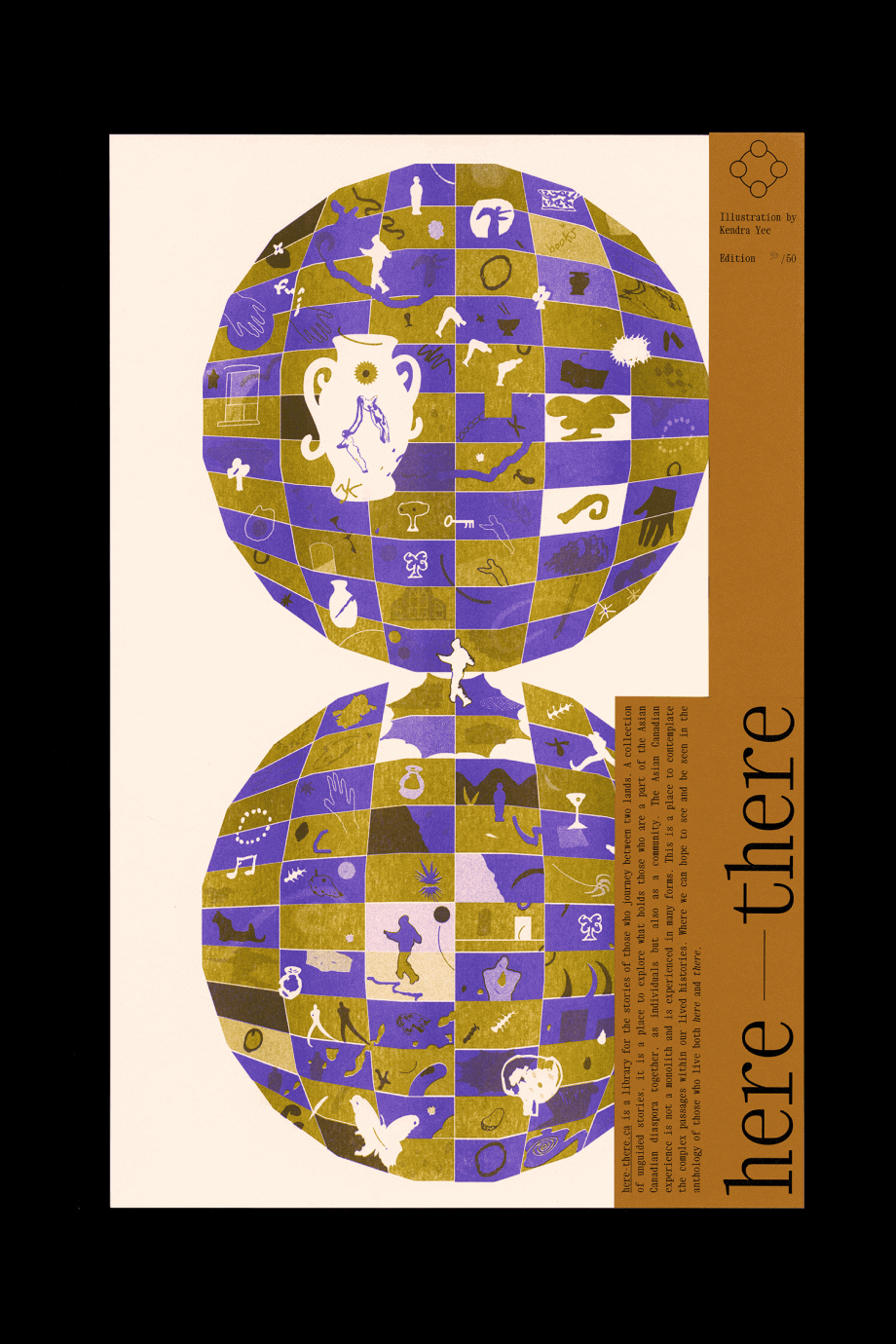

here-there is a library of stories shared by members of the ◌Asian Canadian diaspora. It is a place to explore what holds us together, as individuals and as a community. Each unguided story follows a ◌“pass-it-on” structure that weaves an anthology of lived histories and experiences. Collectively, it is a space to contemplate the nuanced journeys of those who live both here and there.

Story 1

M, Chinese, 27, Toronto

Where are you from?

Play

4:44

AA

(00:00)

Where are you from is such a weird question. I mean, it's inherently racist in a lot of ways I think. And what's frustrating about it is that I don't imagine that individuals who pass as white really have to deal with this kind of question or the implications of questions like this. It's frustrating because it makes me feel othered and like I'm this foreign thing that needs to be named in order for people to understand or for people to get it. It's weird ‘cause I feel like sometimes there's this strange fetishizing exoticism to it depending on who that question is coming from and in what situation it's being asked in. I mean, I think one of the things that I'm relieved about is that it's a question that I hear less and less nowadays. I think people are finally starting to kind of understand what's problematic about questions like this — about making assumptions about people based on what they look like.

(01:02)

Personally, I think it's hard for me because even though I'm clearly Chinese, I … don't really identify that strongly with being Chinese because I grew up in Canada. I was born here, I haven't actually been to China, and I don't know the language. And so while I enjoy Chinese food as much as the next person, I don't really have a strong relationship or connection with being Chinese. Something that's kind of been interesting over the past few years is that I’ve found that more and more this question is starting to be asked primarily by other Asians. Generally it's individuals who are more recent immigrants to Canada or people who are visiting from other countries. And … I think — even though I understand that the question from them is probably coming from more of this desire to bond or connect, it's frustrating for me as well because I think it just brings up this turmoil that I've kind of dealt with since I was a kid about not being Asian enough.

(02:04)

I grew up in a really predominantly Asian neighbourhood, so my experiences are very different from the mainstream narratives that you hear about like those stories, “the white kids bullying the Asian kids for their food or for looking and dressing different” ... That wasn't really what I experienced as a child. And, rather than feeling like, "Oh, I'm not white enough," I felt like I wasn't Asian enough. I haven't really been able to find any or read any experiences — or have conversations with people who have had similar experiences to my own. And in a lot of ways that's been kind of hard because I've … sometimes felt the need to conform to this mainstream idea as well. Not pretend, but act like I had more of this pressure to be white when I was young, which is not at all my experience.

(02:56)

That's definitely changed over time, like as I went into university … I was in my early twenties, living in a bigger city … I think there was definitely more of a pressure to conform to fitting into the dominant culture and being more white. And so there's just been a lot of turmoil over time about how I identify as being Chinese, depending on who I've been around. I think it's only now that I'm closer to my thirties that I've gotten to a point where I've accepted that how being Chinese fits into my identity is going to change over time. And occasionally I'm going to have some conflicting feelings about it. And when people ask me questions like this it's going to just bring up this whole slew of memories and confusion and frustration. But, I think I've really largely accepted the fact that being Chinese and being Canadian are both part of my identity. The roles they play and how they intermingle with each other are going to change and that's kind of okay. I wouldn't say I'm content, but I've kind of accepted that that's just the way it is. And that's how it's going to be.

(04:09)

I am grateful to have gotten to this point though, because I know that a lot of other people that I've spoken to still really struggle with how being Asian fits into their identity. And I think that's something that I would be really interested in asking the next participant in this project. How has your relationship with being Asian changed over time, since childhood? And do you feel like you're similarly in a place where you're kind of at peace with the fact that your identity is the way it is, or do you feel like you're still kind of struggling to figure out how being Asian plays into being you?

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 1

Story 2

M, Chinese-Canadian, 20, Markham

How has your relationship with being Asian changed over time?

Play

7:29

AA

(00:00)

So the question was … "How has your relationship with being Asian changed over time? And, do you feel at peace with where you're at right now with your identity?" To answer the second part of the question first, I would say … I would definitely still feel unresolved in terms of where I'm at. I've definitely become more … comfortable? But it's nothing I would say I'm at peace with yet? It's taken me a long time to get to where I'm at right now, and I feel like there's still so much to go before I'm truly at peace, if I'm ever even there.

(00:45)

So, growing up, I was raised by my grandmother, so Chinese culture was not really something I was aware of, but it was more just a natural part of my identity. It was nothing I ever thought about. It just was ingrained in my day-to-day life. I spoke Chinese fluently. I … participated in customs that were very Chinese without even thinking about it. And it was nothing, yeah, I was ever really made particularly aware of. It was just who I was. And that was all because my grandmother raised me and my parents were away working a lot, so that was all I knew. However, when I started to attend school, I think I was one of the only few, you know, Asian students in my grade. And, that's when I really started to feel different? I really started to notice that, "Oh, you know, I'm not exactly [laughing] like everyone else." The things I do that are so normal to me are very unfamiliar and kind of strange to everyone else. So that's when my relationship with this identity really changed, I think? I really began to distance myself from it. I wanted to keep that part of my life completely separate from my identity at school where I would just try to fit in.

(02:18)

I wanted to like everything else everyone else liked. I wanted to wear the same clothes, eat the same food, and just really, really ingrain and mix with that Western white culture. Meanwhile, at home, I was, you know, a completely different person and I never wanted those two sections of my life to mingle. It just came to a point where I would keep distancing myself and I began to really lose touch with that Chinese, Asian side of my identity. I started to, you know, speak less Chinese at home. I would force my parents to speak English in public especially, and whenever they would try to speak to me in Chinese, I would just be very embarrassed and just, I don't know, just [sighing] really shy away from that, because I felt as if you know everyone was noticing it and staring at us and they would pinpoint us exactly for being immigrants and being different, and not being you know truly Canadian, whatever that meant.

(03:24)

So even now, I feel like I don't really know how to speak Chinese anymore, and when I do, it's very basic. It's just a mix of Chinese and English, and I can hardly speak like a full sentence without English infiltrating into it. So, yeah, there was that point of my life where I was really stuck in that phase of being so uncomfortable with who I was. And then it started to change a bit. When I left home to go to university, I started to reevaluate my identity and really question why I felt so strongly about certain aspects of who I was. You know, distanced and detached from back home life where Chinese culture was so ingrained and almost, you know, I felt like it was forced upon me. It made me come to some realizations about who I was and what I valued, like that feeling that used to make me want to disassociate [was] no longer there, because it felt as if I now had a choice.

(04:38)

And that's when I really started to rediscover that side of my identity and my culture, because it was something I had control over. It wasn't my family making me do anything, but rather I wanted to grow closer to that part of myself. And it really helped having relationships with people who are more open to having conversations about these types of topics. I felt as if I found other people who understood that internal turmoil that I would feel, and that I had been feeling for so long. So having those open conversations really changed the way I looked at things. All these things I've been ashamed of for so long, I started to embrace again. I wanted to learn more about my culture, about my family's history. And … that's where I really, you know, changed my perspective on my identity and this journey I've been taking really switched directions, I guess. Now, I feel like I'm at a point where, although I have accepted a lot more of that part of my identity, I still feel very detached especially with, I guess [sighing] relatives or people who are not my immediate family living in Canada.

(05:58)

I’ve started to think about the pieces of my culture and history that I've been avoiding and missing for so long. There's no longer any personal connection I feel towards them. And — and this homeland that I'm supposed to feel connected to, I have no feeling towards except maybe through, you know, like my grandmother or through my parents. So that's something I've really been evaluating at this point of my journey. I think about if I go back to China by myself, who would I reach out to? I have so many relatives there, but … nothing of substance I would say? Like we don't have any kind of meaningful relationship, and I just become a tourist visiting this country that is supposed to be home of some type to me. So, I guess I've been struggling with … do I want a piece of that home? Is home just Canada? Can it be both, even though I currently have no attachment to this foreign land somewhere in Asia?

And I guess, my question for the next person is, where do you consider home? And, do you ever feel as if you've lost pieces of your identity, and do you want them back?

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 2

Story 3

M, Finnish-Chinese, 21, Toronto

Where do you consider home?

Play

5:26

AA

(00:00)

So the question was … "Where is home for me? And … do I feel like I've lost pieces of my identity? And do I wish to reconnect with them?" So home — home is, and always will be, Toronto. My father came from Hong Kong in the eighties and has been a permanent resident ever since. I came from a mixed background. My mother is Finnish and British, and my dad is Chinese from Hong Kong. Identity and cultural identity has always been a big part of my life, being mixed. From the first kid pulling his eyes back to make … squinty eyes from — from not really feeling like I fit in anywhere in particular. Seeing other Asian kids when I was young and in high school, who I thought I had immediate cultural connections to, probably didn't feel the same way. I think like a main concern was: “I look too white” or … there's an idea of ambiguity to my culture that I never thought of, but was given.

(01:04)

So growing up with Chinese relatives and knowing all my life that these people are my blood, it was hard to take in that other Chinese people didn't see me as Chinese? So that was like a weird dynamic that I always experienced. Always being too white for the Chinese people and too Chinese for white people. In this concept of lost pieces of identity, I think I can really relate too. I'm grateful for the life I've had. For the most part being mixed has had a positive impact on my life. Being able to like experience two cultures from my unique position, right? It's pretty fantastic. But I do feel as though I am missing two halves. A half from my Finnish side, and a half from my Hong Kong side, that I'm just not — so not complete on either end. I guess it was like lack of exposure to either sides of my culture.

(01:56)

From when I was young, I like lived a strictly Canadian life. Like I was never too influenced by Chinese culture or like Finnish or British culture. I visited Hong Kong when I was seven years old and have very vague memories of this event. 13 years later in 2015, I visited Hong Kong again, and this was an extremely positive experience. I learned a lot about — being able to like take in information that I wasn't [able] when I was seven years old was a really great benefit. Being able to learn about my culture and learn about family dynamics I never knew about, my grandmother, my uncles and aunts … This was really positive for me. I just felt a lot more connected. So now Hong Kong feels like almost like a second home. I feel like I can go back anytime. Which is just such a great thing to have just throughout all my life not really knowing much about my culture, where my where my dad came from, right? So that's like the big thing. Knowing where my dad came from and where he grew up and how he grew up was super eye-opening.

(02:59)

Although Hong Kong feels like a second home, there are still some barriers that exist. Such as like a language barrier. And just like culturally growing up, I have different values as even some of my family members. I think a large portion of why Hong Kong feels like a second home to me is because it was a British colony. And I think this like impact on Hong Kong culture where most things are in English now and there's a lot of English-speaking Hong Kong residents — the majority of the population speaks English, right? It's taught in schools. So in my personal identity, I have the colonizer and I have the colonized.

(03:37)

So my British side and my Hong Kong side. And only recently I really understood this dynamic that I have within myself. And even going back to Hong Kong and connecting so successfully with my relatives … there's always just this part of me that doesn't feel fully connected. You know I can never really be fully connected because I am — I'm always going to be mixed, right? There's never going to be a time where I can fully connect with my Chinese relatives, ‘cause there's always gonna be that dynamic of, I'm still mixed. I'm still half white, right? I'll really never have strong connections with my Chinese side ‘cause I just don't speak the language, right?

(04:22)

I never learned growing up. I think my dad tried to teach me when I was young. Living in like predominantly white culture I never really, you know, latched on. It's all just been English-speaking my whole life. And like even my Chinese relatives who live here, we rarely saw them because they lived up in Markham, and that was sort of an on-occasion time. So I never really grew up around people speaking Chinese all the time. Like my dad would, but … it wasn't constant, right? It wasn't a consistent thing in my life from when I was young so I kind of latched on early. And maybe it was like, since I was half white, I could scrape by without having to really understand — understand my Hong Kong heritage and know where I was from.

My question for the next person is: how important [is] this connection to traditional Asian heritage? Is there a way to make new paradigms in how we think about Asian culture? So we don't feel disconnected, we feel connected to a new way of thinking about our Asian identity.

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 3

Story 4

J, Chinese, 20, Vancouver

How important is your connection to traditional Asian heritage?

Play

5:45

AA

(00:00)

The first question was, "How important is your connection to traditional Asian heritage?" And to be honest, I'm having trouble defining what really makes up traditional Chinese culture. My family has always celebrated Mid-Autumn Festival, Chinese New Year, and we did our relatives’ birthdays based on the Chinese lunar calendar. But aside from that, I can't really think of anything that's distinctly traditional. My connection to Asian heritage for me is really accessed through speaking Cantonese. So, I grew up in Burnaby, which is a neighbourhood of predominantly immigrant families. And I lived with my paternal grandparents until I was six. I spoke Cantonese in the house, mixed English and Chinese with my parents, and English to my brother and to my friends and classmates. My parents weren't around a lot. They were working, so I spent majority of my time at home alone with my grandparents and we would practice Cantonese.

(00:59)

My brother, on the other hand — he is three years older and excelled at speaking Cantonese and Mandarin. From an early age, he was put into Cantonese school, whereas I wasn't. And, um, he was much faster at picking up the language and fully communicating to my family. So for a lot of Chinese dinners or family dinners, he would be able to communicate with everyone and understand and respond. Uh, whereas I would only be able to pick up certain parts of the conversation. Growing up, he was constantly praised and I felt kind of inadequate and embarrassed that I couldn't speak Cantonese well enough, when in other times, I was embarrassed that I knew Chinese at all. We both went through 12 years of private Mandarin tutoring, and he really thrived and embraced the language and became practically fluent by the time of graduation. And by age 15, he knew he wanted to move to Hong Kong, and like at that point, we had done maybe five, two week trips in our life? Um, so that was like a decent amount of time, but he knew he wanted to work there after he graduated. And he even changed his phone screen display language to Chinese and his Facebook profile to be his Chinese name. Whereas I had a very different relationship with the language.

(02:19)

And so when I was six, we moved to Vancouver into the city and that was once my dad had his dental practice really picking up. It was in a predominantly white neighbourhood and in a wealthier area. I think this physical shift also marked my kind of shift towards distancing myself from Chinese culture as well. I started to lie to my teachers and classmates about knowing any Chinese or Mandarin. I picked up lots of sports because it gave people something else to think about when recalling me. And I noticed when I moved into the city, that there was this really prominent distaste towards Mainlanders for various reasons. And part of that was foreign investment into our real estate market, and it becoming disastrous at that point. And I think being visibly Chinese or participating in Chinese culture was maybe too much for me because it was almost like it was too close to being a Mainlander. And I, yeah, I really just didn't want to be perceived a certain way, like that had a lot of money to spend frivolously, and had no knowledge of like Western culture. And I think this also drove my distaste towards Mandarin, despite me having been tutored for 12 years. And I really was super apathetic about it and had no intentions of absorbing any of the material because I just didn't want to learn the language.

(03:54)

So last year, I lost my paternal grandfather and he was the person that I felt really was my bridge into Chinese culture. I have deep regrets and an undeniable guilt that I didn't learn enough about his life and as much as I could have, and I can't help but feel like my lack of Chinese language knowledge was to blame. And this guilt kind of drives me to have more pride about my heritage now and has offered an opportunity for reconciliation with Cantonese for me. And now I feel this kind of duty to speak Cantonese at restaurants now and with my relatives in order to feel more connected to my culture.

(04:35)

So the second question I was left with was, "Is there a way to make new paradigms for how we think about Asian cultures so we feel more connected to a new way of thinking about our Asian identity?" And, um, I really don't know. To me ... I feel like becoming more connected to your Asian identity needs to be self-initiated? It has to come from a genuine desire from within. I don't think external encouragement or pressure really will drive this reconciliation and can in fact be kind of counterintuitive in a way because it's such a personal journey and really a choice. That being said, I think a more widespread discussion about diaspora, be it Asian or any group, in popular culture could encourage this process of reconsidering that connection.

So my question to the next person is, do you believe there is a line or point one can reach where you can really feel like you've done your due diligence to learn everything about your Asian heritage?

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 4

Story 5

I, Desi, 20, Toronto

Is [there] a point where you can feel like you’ve done your due diligence to learn everything about your heritage?

Play

5:41

AA

(00:00)

I have been asked, “Do you think there's a line or a point you can reach where you can really feel like you've done your due diligence to learn everything you can about your Asian heritage?” To be quite frank, I think the very notion of due diligence or this idea that, you know, I'm somehow obligated to learn about my heritage simply because I'm a product of it is kind of bullshit. Don't get me wrong. You should definitely respect your history and respect your heritage, but that doesn't necessarily mean that you have to go out of your way to learn about it if you don't feel like it. I think that children of diaspora are often confronted with this dilemma of sorts. Uh, on the one hand, you have the people that you are foreign to, and they have these expectations of you because of how you look, you know, the colour of your skin, the shape of your fucking eyes. But on the other hand, you also have the people who ... are, you know, your “people”, the people that you are familiar to. And they come at you with their expectations of how you should be, or how you should behave, or how you should identify with your heritage. And I think that both of those sides of expectations are equally problematic.

(01:20)

I love my parents and I love how they raised me. You know, they're Indian, they're Muslim. Both of those things have really shaped their ideologies and their set of beliefs. And as a result, they raised me under those frameworks of beliefs. And that taught me a lot of great shit. You know, like, what food is bomb, what Bollywood bops are the most lit, and you know, the bigger things like how to love, and how to trust, and how to think with an open mind. And I'm really grateful for that. You know, I — I really fuck with a lot of the ways in which they view the world. And ... then, what happens is while I do vibe with a lot of their core values, there are some that just aren't for me.

(02:17)

And the hard part is, you know, I respect their values and I respect the way they think and view the world. And even the ones I don't adopt are still respected, but … I don't adopt them. And I don't want that to be in my system of beliefs or in my core values. [heavy sigh] And it really fucks me up because I think about that conversation that I've been putting off for quite some time and will continue to put off until absolutely necessary, where I basically, you know, reveal to them my secret life. And … inevitably I disappoint them, you know? I walk in and I say, “This is what I fuck with. And I know that this is not what you fuck with.” And that somehow automatically equates to "I don't respect you" or "I don't love you" or, you know, "I'm no longer the person that you thought I was". And somehow that makes me foreign or other, or just somehow not right. And I hate that so much because I am so grateful for everything my parents have done for me, have done for my sister. And I know that they have busted some serious ass because being an immigrant in this country is fucking hard. And any immigrant, any child of an immigrant, anyone who's ever really had a conversation with an immigrant can tell you that.

(03:57)

And I hate to think … that by being the person that I'm not expected to be, by not fulfilling the role that I'm expected to fulfill … I disappoint them. I fail them. And that is just so difficult and frustrating for me. But, you know, as much as I hate that I'll disappoint them in this way and I don't know how they'll react, maybe, you know, they'll figure it out and they'll be fucking fine with it. But probably, you know, not, and probably it'll be one hell of a conversation. And as much as I hate all of that, I hate being someone I'm not and being expected to be someone I'm not so much more.

(04:51)

So, that's why I carry the ideology I do with other aspects of diasporic identity too, in that, you know, your due diligence to learn everything you can about your Asian heritage is whatever you want it to be. And that includes no due diligence, that includes no learning, and that includes all learning. And everything in between and anything that I guess lies outside of it. Okay.

So, uh, my question for the next person, um, which is pretty unrelated to everything I just talked about, but, um, I want to ask you, how does your relationship with your diasporic identity affect your relationship with your own sexuality?

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 5

Story 6

A, Chinese-Canadian, 22, Fredericton

How does your relationship with your identity affect your relationship with your own sexuality?

Play

6:37

AA

(00:00)

So the question I got was, “How does my identity affect my sexuality?”, which I think is a really interesting question because it's something I've been thinking about a lot. And growing up in an Asian household definitely affected the way I thought about sex. It was not talked about. The only way I really learned about it was through media, like movies and TV shows. My school taught me some things, but only about like anatomy. And word of mouth, which was the big thing. And I just remember, when I was six years old, I had my first kiss and I told my sister, who told my mom, and she got so mad at me. And basically it kind of set the tone that like relationship equals bad, and then from that point, I felt … scared to express my feelings, I guess? And in turn, I definitely was a late bloomer and I was like, very oppressed.

(01:04)

And even like going through puberty, I even felt guilty for even like masturbating, which is kind of ridiculous ‘cause it's super normal. ‘Cause I was raised not to think about it. And, once I like started getting education and talking about it with my friends more in high school, I was like "Okay, it's not as bad as I think", but I was still so fearful to even explore anything. And it was not until I had this experience where it kind of just like turned me off from all men altogether because it was the first time I ever got fetishized. And I remember this experience really well, ‘cause I was on the bus with this guy who I thought was my friend. And he was talking about how Asian girls have like the tightest vaginas and I was mortified and I went home and I was so confused on why he said that because I did not see my race and my sexuality like go hand in hand like that before. I thought, I was like, "Oh, I'm just a girl. I have a vagina", but no, I'm a female Asian with a vagina. In turn I have a “tight pussy”.

(02:12)

In high school, I barely did anything in regards to sexuality. I just kind of kept it to myself. Even felt embarrassed, like talking about, you know, urges I had. But continuing on after high school and just going off on my own and being more independent, I was embracing that side of me more and kind of just like accepting like, “Hey, this is a part of life. You get turned on sometimes.” And I remember having my first experience with one of my good friends and I just like knew I trusted him and he has known me for awhile and that set the tone for like my future relationships, because I definitely have to know the person and feel comfortable because I was so scared for so long to let anyone in that quickly, just very not like me and I definitely would, you know, just be … so uncomfortable in those situations.

(03:19)

And, going back to like my identity and my sexuality … that question, like in my head, why did the two — two and two go together, definitely increased when I moved to Toronto. You know, being on Tinder and getting like these messages, just like about your race as like the opening line was completely ridiculous. And it just made me angry. Like no white girl would have this issue, you know, no white girl would have a message being like, "Oh, you're so white. It's so hot." That's — that's stupid. That doesn't happen. But it happens to … it happens to me. And it just really made me mad and upset just like seeing this and then hearing my fellow friends who are also Asian go through this issue too.

(04:15)

And … you know, when I started again re-exploring my sexuality in Toronto with someone I trusted, I was really hyper aware of, you know, does he see me for my race? And I think deep down, I kept saying — asking in my head, like, “I wonder if he sees me for my race or he looks at me as a normal person.” And it was really weird being hyper-aware during that time of that fact. And, you know, I did ask him once, like, “Do you see me as Asian?” And he was really quick to respond like, “No, like I only see you as you”, which was comforting to hear, but you know … there's so many people out there actively seeking for a certain type. And I just don't want to fall into that “trap” because people are people and race should not come into factor when you, when you're looking for a partner, you know. Like I think that's so sketchy and ridiculous to be like, "Oh, I'm only attracted to a certain type of race."

(05:33)

Overall, I'd say my sexuality and, you know, being Asian … in my head, I don't want them to go hand in hand, but when it comes to like being in the real world and dating, you know, that's something I automatically think of. I have had thoughts about, "What if I was a different race?”, “What if I wasn't Asian?", “How would my whole world change in terms of my sexuality?”, “How would my experiences change?” And I think that also has affected my relationship with my body because I tend to put two and two together. You know, my insecurities in terms of my sexuality, you know, does stem from how I see myself.

So, I guess my question for the next person is, how do you find that your diasporic identity affects your relationship with yourself in terms of body image and how you see yourself?

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 6

Story 7

L, Filipino, 20, Toronto

How does your identity affect your relationship with [your] body image and how you see yourself?

Play

4:14

AA

(00:00)

So the question I got was, “How do you find that your identity affects your relationship with yourself in terms of body image and how you see yourself?” I do think that being Asian has definitely played a role in the way that I see myself and the ideals that I feel like I should abide by. So one of the things that I can remember from my childhood is the ideal that I had to be a lighter skin tone. That idea was pushed down my throat a lot as a kid. And as a result, I stayed out of the sun more, played less outside, and I also used whitening products that “help keep your skin lighter” or make you even whiter. And thinking back it was just such a weird thing to me at a young age. I couldn't understand the reason why I would have to go to such measures to be a skin tone that I was not. But to the people around me, it was so normal to be taking such measures to just be this lighter person or lighter version of you.

(01:28)

And at that time, I didn't know how to educate them on the fact that skin tone honestly does not matter, or it should not matter at all. I think that there's definitely a difference between the way that my parents see themselves and the way that I see myself given the experience that I had growing up in so many different places. Whereas my parents who solely grew up in the Philippines where those same ideals are pushed down their throat. And if I were to give it a reason as to why they think they should be this skin tone, I think it's because of the different people or the different countries that colonized the Philippines in the first place. They were usually someone of a lighter skin tone and those people were glorified. And as a result, people in the media — those who are popular basically, usually carry a lighter skin tone and are kind of favoured over those who are darker.

(02:41)

I don't think that this problem could really be solved overnight or resolved over a few days. I think that it's an ongoing change that has to happen. And that awareness has to be risen about these different things. I wasn't really comfortable in my own skin for a while and I really found gaps in the way that an Asian or Filipino is supposed to look like, and how I looked like. I think that growing up in a different place really played a big role in this and how I see myself. I didn't grow up in the country that I'm technically from, or what my ethnicity is. I grew up in Dubai and Canada where there are many different kinds of people from many different kinds of countries, and so I felt like it was okay to be different at times, because these people all look different from one another and I looked different and that was okay. But yeah, I do think that my diasporic identity affects my body image and how I see myself.

But what I'm interested in asking the next person is, how does your diasporic identity affect your educational or career-related goals? Was there ever an expectation of what you should be or do in terms of your grades or career choices?

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 7

Story 8

C, Vietnamese, 21, Toronto

How does your identity affect your educational or career-related goals?

Play

8:51

AA

(00:00)

I was asked, “How does my identity affect my education or career-related goals? And if there were any expectations I had to fulfill in terms of my grades or my career goals.” And I think my identity of being Asian has affected that aspect of my education and my career path at a certain point in my life. It's definitely affected my perception of who I was going to be or who I thought I should be, and me basing my life around these expectations. If I look back to my childhood and think about how these expectations were created, I would say it's from my parents. They had high expectations at a point, but when I was a kid, they were pretty lenient on how they raised me. I was the youngest out of four, and I guess they got a little bit lazy with parenting and didn't impose that hard work mentality on me.

(01:12)

I think if anything, I gained it over time and we never really did those extracurricular activities with sports or learning a musical instrument, probably because of our low income. But we did go to Kumon for math and reading comprehension. So I don't know if that counts as it, but um, I think that stereotypical career goal of, you know, becoming a lawyer or doctor or engineer, anything in like sciences or getting like that financially stable job, it was more imposed on me by my relatives. And, uh, if I remember those family functions, my older aunts and uncles would always be asking, you know, "What are you going to do when you grow up?" And they would suggest those titles and those jobs. And it was really random because they weren't really interested in me or my hobbies or my opinions. It was more of like a one-upping show where they were judging, like which kid is going to be more successful. And I would always answer with, “Becoming a teacher,” just because I thought it was a good enough answer and they'd stop questioning me.

(02:37)

And I think with the second part of fulfilling those expectations within grades, I always feel like I need to do the best I can. Try to do the best when it comes to grades. Not necessarily getting high marks, but being invested in it. I know that if I'm not interested in the subject, I at least try to do the best I can. And it was important to me in elementary and high school. I thought it was a way to make my parents proud. I find that the lack of communication I had when I was younger, it was hard on me. And at a certain point I lost the language and it was difficult for me to speak Vietnamese back to my mom and dad. So I thought if I got a good grade, they would be happy. And I think I'm slowly getting out of this way of thinking where, you know, you're valuing the number, but that number shouldn't be dictating your life or who you are. And right now I'm just focusing on passing and getting that credit.

(03:59)

I think my diasporic identity really hit me when I was a teenager. And I remember it was my final semester in high school, and we were supposed to choose our colleges or universities to apply to for the next year. And you were choosing who you wanted to be in your career. And I was set on going to art school, like my older siblings. And I'm lucky because they paved that path for me. They were able to make that an option that was sort of acceptable by my parents. But when I told my dad what I wanted to do, he was really disappointed. And I remember going to my guidance counsellor, and I tried to reschedule my semester with calculus, chemistry, and physics so I could have that option to apply to university. And that would give me a job that was acceptable to my parents, that financially stable job. But luckily, my guidance counsellor, she told me, "No, you can't listen to your dad and you should stick with visual arts," because she saw it was a passion of mine. I think I felt that pressure because I was sort of the last one out of the bunch of kids, sort of this last hope. And I didn't want to let my parents down. Like they wouldn’t support me in that decision, but I talked to my siblings and my friends and the people around me and they reassured me it was the right path, even — even if it meant disapproval. And if I look back, I think it's not fair, you know — not fair in a way that I would be sacrificing my dreams, whereas my siblings could achieve theirs. And if I did go back down that route, I would have totally dropped out and go back to art school.

(06:05)

And I think about where I am right now with my education and me getting my Bachelor's of Design. It's the right — it's the right one. Even though I have no idea where I'm heading, which is still exciting and scary, but I’m three years into it. And my parents are a little bit skeptical about that choice and they don't really know what I'm doing. If I say I'm a graphic designer, they don't really understand that title. So I kind of cheat and I say, “I'm doing a little bit of advertising.” And … I don't know. I feel like their opinions and expectations are always going to be there. But I think I've gotten to a place in my life where I'm happy doing things for myself, and I'm making those choices for myself because that means I'm growing up. And it wasn't an easy acceptance for them, but they eventually did accept it.

(07:09)

And it's weird to me 'cause it's — it's this psychological aspect of like fulfilling their expectations and needing their acceptance. Like that's really weird and it's not really easy to ignore that feeling, like you're disappointing them in that way. And I think these ideals and expectations are created because they want a better life and more opportunities for me. My parents immigrated after the war in Vietnam and my dad has been working a blue collar job ever since he came to Canada and he's still working hard. So I think that's why I feel like I need to push myself to do the best I can because I can't let him down. And they sacrificed so much for us.

So, you know, following that, I want to ask the next person, how does your diasporic identity influence your dynamics within the relationships of your family? And if there's this barrier you're trying to overcome, if, you know, you had any challenges where you try to express your sexuality, your opinions, and views. And is it possible that maybe you've hidden a bit of your own identity because you don't think it would be fully accepted or understood by them?

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 8

Story 9

A, Chinese-Canadian, 20, Durham Region

How does your identity influence your dynamics within the relationships of your family?

Play

9:30

AA

(00:00)

So the question that I am responding to is regarding how my identity influences family relationships and if that served as a barrier in those relationships, if it brought about any challenges, or led me to want to hide pieces of myself. Honestly, it's a very fitting question for me I think. I'll just start by giving some background. So my parents are immigrants, so I'm first generation. My parents came to Canada when my mother was pregnant with me. So, they're functionally the only family that I have. Obviously I have a lot of extended family back in China, but … I don't know, family seems like a generous word because I've — I've met them a handful of times in my life. So yeah. I just … I want to preface this, uh, anything that I'm about to say with the fact that I am so, so, so grateful to my parents for all the sacrifices that they made. They threw themselves into an impossible situation by coming to Canada, without knowing the language, without really having any job prospects, without really knowing anyone. Not really, at all, I think.

(01:28)

But yeah, I don't know, logic only takes you so far. And at the end of the day, I still do feel how I feel about how they — they treated me growing up. So yeah, the way that they treated me growing up was super traditional Chinese parenting. Um, really living up to all the clichés from high pressure to succeed academically, a lot of pressure to excel at piano and advance quickly, not being allowed to see friends except for on the weekends, and not being allowed to have male friends. Like that sort of stuff, et cetera, et cetera. So, that kind of parenting always caused a riff, especially when I compared my experiences with — with my, well to be blunt, my white friends. And all my friends were white because I grew up in a puny town where literally there were maybe two other Asian families. So there wasn't a lot of representation.

(02:33)

So yeah, like a lot of tension and a lot of conflict stemmed from cultural differences and personality differences, uh, that I had with my parents. And even language barriers was a big issue. Like my mother particularly, she … she just never really picked up the language and that's partially because — to no fault of her own, obviously. At her workplace, like my town’s — my town’s very ignorant as a whole, I would say. And even the adults could be cruel, and at her workplace she was bullied for her accent and the way that she talked. So because of that, she, I think, shied away from using her English too much. And it's just kind of a self-perpetuating cycle of the less you use your English, the worse it becomes. And then that affected her ability to communicate with me because I don't speak Chinese because I was raised in a white town. And then the worst her English got, then the less she'd want to use it, and et cetera, et cetera.

(03:46)

So I was stuck in this strange dynamic where I was so different fundamentally than my parents in almost every way. And to add another layer of complexity to that, I couldn't even really communicate with them. So yeah, my, my relationship with my parents has always been kind of tense. And … I don't know, it's something that always made me kind of sad that I never got the — the “classic mom experience”. Like I never trusted her enough to ask about boys or, or I never went to her when I was being bullied at school, or when I started struggling with my depression. Like that was always just something that I dealt with on my own or with the support of my friends.

(04:37)

And my dad was always just kind of in the background. He played more of a role for comedic relief, if anything. But in the times that it was serious, he just got really like quiet, or would leave entirely. And he's the one with the better English too, so that was an interesting dynamic that was made; that I was communicating with someone who … who didn't really understand what I was saying. And that would obviously amplify issues because she would — something that often happened was she would listen to what I was saying, only understand keywords, and then draw assumptions about what I was saying from those keywords. Anyway, tangent. [Laughs] Um, the point is I, I, from the dynamic that existed between myself and my parents, I learned to deal with a lot of things on my own.

(05:31)

Honestly, sometimes it feels generous to even call what I have with my parents “a relationship”. I don't know. I know that sounds cold, but I just mean that we don't — we don't really know each other. And we weren't really right for each other, especially when I was growing up. And I know that's, that's nobody's fault, but … like they tried their best. And like, like I tell people, my mother is so, so fucking brave for, for doing what she did. My dad too. But like, my mother left behind everything. And I know my dad did too, but she was like, she was pregnant. She was so close to her mom. All her friends were there. She was thriving there. She had a job that she loved. She didn't know a lick of English, and she came here. And then she had to be a first time mother in a country where no one understood her. Where no one cared for her. I don't know. Like she — she had to go through a lot.

(06:40)

And I'm not trying to negate that or trying to take that for granted. But at the end of the day, the, the conditions just weren't right. Their, their traditional Chinese parenting felt almost like, I guess, abusive when I juxtapose it to the parenting of my friends. And they were always working at odd hours because of course they had to, to be able to financially support us. But because of that, I never really saw them. So they never really planted themselves in my life as parents, which is why I think I have such a … a different relationship with them. Even in comparison to some of my other first-generation friends with Asian parents. And I never learned the language because of so many like little things — like Mandarin I mean. I never learned Mandarin because of so many things that just never fell into place, I guess.

(07:35)

And I'm sure my, my teenage years didn't do anyone any favours. So, I don't know. The conditions weren't right. And part of it was my fault, part of it was their fault, part of it was just the situation. I don’t know. I guess what I'm trying to convey is that my relationship with my parents isn't where I wish it was. Yeah I don't know. It's not like the movies where you see the teenage girl going home to her picket fence house, and her mom and her are best friends, and they share everything. And when she's upset, she goes to her mom first, and she cries on her mom's lap while her mom holds her and tells her it's going to be okay. Like that's not something I ever had, and that's not something I think I'll ever have. But … but that's okay, because I don't blame anyone for that.

(08:28)

It truly is not anybody's fault. I'm growing every single day. And I'm so happy with who I am, and what I'm doing, and the friends that I have. And this is my reality because of the sacrifices that my parents have made for me. So yeah.

My question for the next person is kind of in the same vein. If you're first-generation, I guess the question would be, uh, do you ever feel any guilt for the sacrifices your parents made for you? Because I don't know, I know I certainly do. My mom truly would be so much happier in China, but she gave it up for me. Or maybe that's too specific a question, I guess. Were there ever instances of feeling guilt because of something you said to your parents out of anger or, or realizing you didn't appreciate them as much as you should, or … I don't know. Something like that.

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 9

Story 10

W, Chinese, 22, Hong Kong

Do you ever feel any guilt for the sacrifices your parents made for you?

Play

5:25

AA

(00:00)

I was asked if, "I was first generation, and if I ever felt any guilt for the sacrifices my parents made for me? Were there any instances of feeling guilt because of something I said to my parents out of anger? Or realized I didn't appreciate them as much as I should." My mom was born in Indonesia with family all over Singapore. She married my dad in Hong Kong and that's where I was born. I moved to Canada when I was 11 in grade five with my mom and my brother. My dad stayed in Hong Kong for another year before moving here with us. I didn't know we were moving until just a couple of weeks before leaving, and I remember not fully understanding the concept of immigrating either, except for the fact that Canada was really, really far away from Hong Kong.

(00:47)

I vaguely remember my mom asking me when I wanted to get on the plane and I picked the dates just before my winter exam, so I didn't have to study during the Christmas break. In Hong Kong, I was always considered a good student with great marks and many friends, so it was very isolating when I became a student needing a translator and having to go to a separate classroom for ESL classes. It was especially hurtful, and people would repeat certain words I say because of my pronunciation, making me hyper-aware of my accent. I would be teased for finishing my projects earlier than the due date, for being a nerd, or being a FOB.

(01:26)

I remember one time in grade six, I had to do a presentation in French and I started crying in front of the class because I didn't know how to pronounce any words correctly without my accent. It was in the same year that my ESL teacher pulled me aside and said I was ready to leave ESL and be introduced to the regular classroom. I again started crying because I was so afraid to be made fun of and leave the only comfort zone I created for myself of ESL. I tried to distance myself as far away from the label of being an immigrant as possible. I used to crop out any Chinese words you would see in photos before I posted them on Facebook because I wanted so badly to fit in.

(02:10)

My dad was an airplane technician in Hong Kong. He had a pretty hard time adjusting to a life of living in Canada, and was unemployed for a very, very long time. We lived in a basement in Markham and had a really shitty white Toyota that I was embarrassed to be seen with. So embarrassed, I would tell my mom to drop me off a couple of blocks away from my school, just so I wouldn't be seen getting out of it. I remember being in a car driving home one night after another unpleasant basement hunting experience. My dad was complaining something about money and I got so frustrated about him being picky about the jobs he was looking for, that I took the career section of the newspaper and just threw it at him.

(02:53)

My brother was 14 when he first got here and also had a pretty hard time adjusting to going back to Elementary school, when he had just graduated from one in Hong Kong. We never had a good relationship. He would say pretty awful things to me and I always learned to ignore it. Eventually we just disregarded each other's existence completely.

(03:15)

We moved a lot in the first couple of years. My mom and dad separated when I was 13, and my brother was admitted to the hospital for treatments of psychosis. I rebelled pretty hard, especially from grade six to grade nine, when I almost never talked to my mom other than the bare minimum and necessary conversations. I basically ignored all the drama that was happening in my family, by going out all the time with my friends and never going home until really late at night. There's an unspoken rule where I don't ask and she doesn't tell. So to answer the question ... I almost feel guilty for saying I don't feel much guilt, but rather a lot of resentment towards my parents moving to Canada in the early years. Of course, I love Toronto now. And I'm really grateful for being a Canadian, but I often wonder what cost my family traded status for. They moved here because they thought we weren't able to get a good education in Hong Kong. But when I reconnected with my friends from my childhood, many of them seemed to travel to more places than I have, experienced more of life than I have, secure a job after graduation faster than I have. And I always felt like my family never lived up to the immigrant dream many people have envisioned for themselves, and I certainly am no lawyer or doctor or engineer either. We never talked about it, but I wonder often if my mom has any regrets about moving here.

(04:47)

My maternal grandpa passed away when I was in grade eight. Luckily my mom was able to be by his side during his last months, but it's still really heartbreaking when Hong Kong was just so much closer to her roots than Canada is. Things are obviously a lot better now. I have a great relationship with my mother, and I'm really, really proud of who I am as a person, as an immigrant, and as Chinese. I'm visiting Singapore in the next couple of months. And I'm really, really excited to be seeing all my family, and understand more of my roots.

To the next participant, have you ever felt embarrassed about your ethnicity and in what ways you cope with your insecurity?

Initial Submission Date: 2018

Story 10

Story 11

J, Korean, 24, Toronto

Have you ever felt embarrassed by your ethnicity?

Play

7:11

AA

(00:00)

So by the last participant I was asked, “Have you ever felt embarrassed by your ethnicity and in what ways do you cope with your insecurity?” I think the earliest memory of being embarrassed by my ethnicity is probably when I first immigrated to Canada. That was when I was a literal child coming to a country, not knowing the language, not knowing anything, not even knowing why I was going. And, at the customs office I remember it was just chaotic. Everybody was just loud and also I could tell that my parents had no idea what was going on. I could tell that they were lost as much as I was. I could tell that they had no idea what was going on because they didn't understand a lick of English. I think that was the first time I've ever seen my parents so vulnerable and kind of, human, that they could no longer protect me in a sense. That kind of ... weakness? That kind of powerlessness really struck a chord. I was ashamed to not understand what was going on, but I had no power, to kind of communicate or to even have a voice at that point.

(01:24)

It didn't help that I was like, I grew up kind of being taught that Korean people were powerless, right? That, we come from a small country so like we have to work much harder to kind of, create a voice for ourselves or to be internationally recognized. It always felt like an inferiority complex that makes sense from their perspective and also from, I guess a start perspective, but it kind of ended up feeling a little bit personal when it didn't need to be in a sense? Or maybe that's just me not understanding it because I've been disconnected from that part of my identity as I moved here. I felt like, my personal embarrassment or my kind of insecurities with my ethnicity originated with that otherness, but from a personal level. I think the first time I kind of felt this otherness, of me being the other really was probably when I was in middle school.

(02:31)

I was the only Korean kid, the only Eastern Asian kid in the entire school. I didn't really care, or I guess I pretended not to care and I was fine with it. I still made friends. I still had a good experience, but I could tell that there was a bit of a dissonance. I was a little bit ostracized. I grew up a little bit differently, right? But, I think that's when I really realized, "Oh, I'm different because I'm Korean. Because of my ethnicity, I'm being left out. I'm being ignored here and there." Thankfully, I guess in a way I didn't necessarily have to cope with that because by the time high school came around, I moved to a community where there was a greater Eastern Asian population.

(03:28)

But, even kind of transitioning back here, I was just kind of a little bit thrown off with no Koreans whatsoever being around and then everybody being either Korean or Eastern Asian, that I felt a little bit awkward? That I was the other again? Not necessarily just because I moved back, but more so because I felt like I was overcompensating for being Korean. I was like, "Oh, I love Korean things now, Korean things are so good." I think, especially now I feel that as well with the success of Korean media, such as like Minari and Parasite. On some level I love that my ethnicity is gaining recognition and our voices are finally being heard. But at the same time, I also see people that are overcompensating with this and kind of trying to feel superior because of that inferiority complex that I've mentioned before. It feels like people are just trying to put others down just because of it. And it's, it's a little bit odd because I can see that from both Korean-Canadian people and also Korean people. Definitely a little bit less with Korean-Canadian people just because they live in a multicultural society, they understand how people interact with each other without that kind of homogenous society perspective, right?

(04:54)

But I think a little bit of the embarrassment with my ethnicity comes from actual Korean people in Korea as well. It's a little bit problematic in the sense that because they're so, kind of closed off and have that mindset of like, "We need to stick together. We need to create something. We need to show something. We need to prove something." That, they antagonize so much of the other that it becomes a little bit, I mean, it has racist tendencies obviously. But I think even within their own country and their own people like the hidden camera stuff that's going on and the whole anti-feminism movement in Korea, it's just ... it's like seeing stuff like that definitely makes me feel embarrassed to be Korean in a different way, a little bit more ashamed. But I think that's also maybe just something that happens with every country. It's not necessarily just Koreans.

(05:55)

I think to cope with that most likely I think I either try to find parts of Korean culture or my heritage that I resonate with to either balance out the negative with the positive. Or either, I just look outward, try to find things that resonate with me that I can confirm to myself, “Oh, I as a person don't have to consistently be Korean in the sense where I agree to those values”. It's more so that I am Korean, I am Canadian as well and that kind of mesh, I'm allowed to be my own individual. But I'm sure also there's a bunch of Korean people that disagree with all of these actions as well. So, I think there's a little bit of work that I probably have to do to overcome also my own insecurities a little bit, without having to differentiate myself with Koreans as well.

So, for the next participant, my question is, do you distance yourself from your ethnicity or is your ethnicity something that is so close to you that it would be something that you introduce yourself to strangers with?

Initial Submission Date: 2021

Story 11

Story 12

E, Filipino Chinese, 24, Thornhill

Do you distance yourself from your ethnicity?

Play

4:37

AA

(00:00)

So the question I was asked was “Do you distance yourself from your ethnicity or is your ethnicity so close to you that it would be something you introduced yourself to strangers with?” My answer to that — I mean, I don't think I would ever introduce myself [laughing] with my ethnicity [laughing] because I don't know I don't think that's really relevant when you introduce yourself to someone. But ... whether or not I distance myself from my ethnicity — I mean, no, I don't distance myself from my ethnicity. Like I'm proud to be Asian. But to be, I guess, a bit more specific, I guess I have a yes and no answer to this. So I'm half Filipino, half Chinese, but I've … my, my childhood has mainly ... I've mainly had like a Filipino upbringing, I guess you could say? So I moved here when I was 18 months old, when my dad and some of ... and a few of his relatives moved here to Canada.

(01:14)

So, pretty much all of my relatives in Canada are Filipino. So the ones that I see at Christmas parties, birthdays, all that, um, it's always been celebrated in a Filipino kind of way with the karaoke and the lechon and all this — I dunno, good Filipino food. I'm proud to be Filipino. I have a lot of people I can relate to. You know, representation matters. Like I — I see myself sometimes in shows in like Kim's Convenience, Crazy Rich Asians, whatever, all that. So, no, I don't distance myself from being Filipino. But with my Chinese side I guess I kind of involuntarily have distanced myself from that? And I guess I wasn't really aware until … I don't know maybe in my like teenage years I kind of realized like, a lot of my Chinese side — so my mom's side, my mom grew up in the Philippines, so she doesn't really have that much of Chinese culture like embedded into her. She speaks Tagalog, she's immersed in Filipino culture.

(02:28)

So my Chinese side hasn't really been as like a dominating, or a prevalent thing in my life. I mean I do still identify as Chinese, like Filipino Chinese, that's what I always say when people ask where I'm from. But, I mean I guess I would want to know a bit more of like my Chinese side. Like why, did you know whoever from my Chinese side move to the Philippines? Like, who was it? Like my great-grandfather? Great-great-grandfather? My grandparents? Like I don't know. And my mom, I guess my mom, doesn't know either, for some reason she doesn't really have like a good — she doesn't really have that knowledge of like her background. Which is kind of like a bummer. And, I don't really talk to my — I mean I talk to my grandparents and some of my relatives through other relatives on Facebook.

(03:25)

So, not too much of like good communication between me and my grandparents and with COVID, [sigh] I was actually supposed to go to the Philippines in the summer, so that would've been like a great time to reconnect with my family. But, of course because of COVID that didn't happen. But yeah, I would like to know more about my Chinese side. Like, I think it's important to know where you came from, like regardless of how prevalent it is in your life. But it's nothing I'm really losing sleep over. Like, I — I'm perfectly fine, like with my, my childhood and my upbringing and the way I was raised. For the most part. Um, [laughing] so, no I wouldn't distance myself from being Filipino or Asian and yeah, I'm perfectly fine with that.

So, for the next participant, my question would be, how do you think your Asian upbringing or lack of has benefited you or hindered you?

Initial Submission Date: 2021

Story 12

Story 13

R, Korean, 24, Vancouver

How do you think your Asian upbringing or lack of has benefited you or hindered you?

Play

7:16

AA

(00:00)

My question is "How do you think your Asian upbringing or lack of has benefited you or hindered you?" When, I think about this question the first thought that pops into my brain [laughing] is, you know, "what exactly constitutes an Asian upbringing?" For myself, I was born in Korea and I immigrated to Canada when I was young with my family, but I grew up in a very atypical way that most Korean kids I saw grow up in my community. First and foremost because I was raised by a single mom. And, you know I think one could say that Korean kids typically are brought up in quite a patriarchal sense in that kind of like traditional family mold. And even the fact that my parents, separated and divorced after we immigrated was a bit of a scandal in the Korean community, um, that we grew up in because there's just such a strong sense of survival mentality that's instilled in you as an immigrant family. That when you arrived, you're having to deal with so many external challenges that, you almost have to suppress a lot of the issues that stem from very complex family dynamics, because you have to face all these external issues and challenges.

(01:25)

And there's just an immense amount of financial, social, and cultural pressures and expectations to stay together as a family to survive in this new environment. So, yeah I think in that way, you know, I was still brought up Korean, but it definitely wasn't your typical way of growing up in the Korean community where I was. So, yeah, but we still had a lot of the similar challenges growing up in terms of the pressure to assimilate. Like my mom was quite strict about banning a lot of Korean content in the house so that we could really immerse ourselves in the new language and the new culture.

(02:16)

Yeah, we almost had to like hide Korean books as if they were contraband around the house. It was like really odd and I think continuously having to go through cycles of that as a kid you're almost taught to be shameful of some aspects of your culture, which is really unfortunate. And I, I don't put this, or resent my mom, for making these decisions because I think, you know in her eyes, it's just, like there's just an immense amount of pressure and fear that your children won't, be respected or fit in, or like kids will make fun of them. And I just think it's a little bit sad that we, almost began to like equate recognition and respect in that way to increasing our proximity to, you know, whiteness. That we were just so fearful of being diminished, that we abandoned so much of who we were.

(03:13)

And as an adult I think, you know, I don't really see those aspects of having hindered my development because now, having to want to reconnect to different aspects of my culture it's just been a huge part of my growth and development. Now that, yeah, I don't know if I'd really call it a hindrance in that way, but it is interesting just to see what it's done for the development of my identity personally. Just, seeing that, I had to hide a lot of who I was and embrace this new culture and this new country, essentially. That you're always — or I you know always wanted to find this like sense of belonging and, I went back to Korea for the first time in a decade, a few years back, and I realized then that, I couldn't place that exact sense of belonging on a certain material location.

(04:11)

Because when I went back, you almost feel like you should have this reckoning that you've returned home because you're finally in a place where you're surrounded by people that look like you, you can speak their language, you can enjoy the same food, listen to the same music, but that's not the case at all. [laughing] My identities are just so complex anyway. I don't think you can be solely just one thing and I definitely, [chuckle] am not solely Korean or solely Canadian whatever that might mean. It's just, embracing those different aspects and having this intermingling of different identities and embracing that and learning to embrace that, that's just like a continuous process. I will say, a major benefit to how I was brought up was, just the immense sense of community that I felt. I think when you're othered in the mainstream it's just, you've learned to take care of one another in a way where, that community becomes your safe haven to enjoy your culture, to enjoy food and share cultural references [laughing] with and things like that. Which I loved.

(05:22)

And you created so many special memories with that and especially growing up in a single parent household, my mom would work from 7:00 AM to 10:00 PM when I was growing up. And when I would get sick from school and things like that, I knew that I always had someone to call that would pick me up. So, yeah we really took care of each other and supported each other in that way. And because of how much love I have for my community, I just wish that there had just been more conversation and dialogue about topics like mental health. And, that's still just a hope that I have for my community now. And reflecting back, a lot of it just has to do with the fact that there's just such a language barrier that, sometimes you don't even know that there are words to describe the, experiences and feelings that you have and to validate them.

(06:15)

And also just translating that from English to Korean or vice versa, I think is really challenging and a barrier in that respect. And there are a lot of other barriers to the topic of mental health among, you know, Korean communities and just immigrant communities, I think in general. It can also be the fact that you can't take off time, off of work because you have to support yourself and your family. And, you know, you can't seek support. You don't have the resources to seek support in whatever way that might be. So I, I kind of, want that dialogue to open up to learn, how we can better support one another in that way and to just be more honest with each other in a lot of ways as well.

And so my question for the next person is, how is mental health talked about in your community, if at all and how does it impact you?

Initial Submission Date: 2021

Story 13

Story 14

S, Sri Lankan, 23, Toronto

How is mental health talked about in your community?

Play

7:23

AA

(00:00)

So the question is "How is mental health talked about in your community, if at all, and how does it impact you?" I know that this will be true for many immigrant families of varying backgrounds. The short answer is, we don't really talk about it because when we do, we are often seen as failures. We don't feel successful. We're failures that are ungrateful for what our parents have worked so hard to give us. We’re failures because we, are bowing to pressure that has been on our parents all of their lives pressure that our parents have, navigated and moved past. We're failures because, we've been coddled in this modern-day society where everything is handed to us. So the fact that we have problems is ridiculous because we couldn't even begin to imagine how much trouble our parents went through.

(00:52)

So in my conversations about mental health in particular, my parents often cycle between, “I can't believe you're like this what did we do wrong?“ And “if this is so stressful for you, I don't know why you're even bothering trying you’re clearly never going to go anywhere with that mentality.” And these conversations really grind my gears to say the least. They just make me so angry, because I'm being so vulnerable in the moment that I have them and I'm ashamed of being vulnerable because my parents are never vulnerable around me so I grew up feeling that way. But I also in the moment, I'm talking about it because I need to talk about it I feel like I'm going to explode if I don't. I feel like I need to defend myself, I need to react to the pressure that they put on me. And so I want to come back to these themes of I guess — failures, being a failure and like measures of success and — mindsets because I feel like these two things really explain why people in my community don't talk about mental health.

(01:51)

So I spent a lot of time, trying to understand why mental health was such a taboo topic for so long. And I'm definitely over-analyzing, when I talk about this, this is probably also not the most astute analysis but I've come to some conclusions. So, thinking about these metrics of success, thinking about the type of mentality that immigrant parents have had to have over the years, thinking about the idea that us kids today, haven't gone through the trials that immigrant parents have put themselves through, without a word of talking about mental health. So some of my earliest memories are being told that only non-religious girls feel anxious and depressed and if I were closer to God that I wouldn't feel that way. And as wild as that sounds, it's interesting because it's a very survival mentality.

(02:41)

When you go through losing your whole community, moving to a new place, where they don't accept you, nobody speaks your language. You increasingly fall back on coping mechanisms and for people in my community that was religion. Religion was a way for people to come together to be accepted and interestingly, because of this people went from, being very liberal about the way they practice to more conservative. Because, by coming together at the religious centre, their community was much more close-knit. Religion is also, a way of coping with struggles in your life. And so, in this quest for acceptance, religion brought them together and religion was the way that they dealt with all of their problems. It became a very personal way of dealing with problems because back then everyone had problems you know. Your struggles weren't unique, a lot of other people were struggling, you just had to do what you could to get by.

(03:33)

But that quest for acceptance wasn't just, something that started when they immigrated here, it's something that stems from way way back in Sri Lanka because, there whiteness was paramount to class and refinement. The British really split up different religions, and implemented the caste system on top of all of that to create divide between communities. By elevating certain groups, and by ignoring other groups, and by putting themselves at the top of this pyramid, they really did break up the country and control it in a very effective way. And this is true of India, this true Sri Lanka, this is true of many colonies that the British had.

(04:11)

The people who went to the white schools, the people who, learned English, who dressed like the British, who went abroad for school, that was refinement. That was class. Interestingly that quest for acceptance, that survival mentality, isn't new and specific to Canada at least from my community, they're going from colony to colony from colonizer to colonizer. They grew up trying to be more white, to be more British, to elevate the status of their family. Learning English, going to an English university, that was the way to get ahead. And they came to Canada because they wanted to use those skills to have a new life in a place with more opportunities. And the reason there are more opportunities is because whiteness is entrenched in the way that opportunities were given and are given. And I know this sounds, you know, like over-analysis, but I really do just think back to the comparisons of good behaviour and good thinking I guess, that I was fed as a kid. My dad would constantly compare me to his white colleagues' children, and whenever he spoke of intellectualism or refinement, those were the examples that he used.

(05:19)

And so it made sense to me that my dad compared me to his white colleagues' children so much because he grew up making this comparison of himself. So to me, the reason that people don't talk about mental health in my community is in part because of the face that they're trying to put on for others. It's about this arbitrary measurement of success that doesn't include talking about your problems or having struggles or struggling. It doesn't include being vulnerable. It's about their own upbringing. They're fighting to survive in their home country. They leave their home country and they're fighting to survive in a new country to give their family a better life, to be accepted. It's also about their own families and the conversations they didn't have.

(06:03)

So my mom is actually an immigrant to Canada. She immigrated when she was eight years old. And because of that, she grew up with a language barrier between her parents, her parents were busy and so she really just had to solve her own problems. Like she couldn't talk about things that made her upset and unhappy. She was a problem solver because she had to be to survive. The previous speaker talked about that survival mentality. And I think that's ultimately what it comes down to here. My parents didn't have time to talk about mental health because they were too worried about surviving. And so they dismiss what I'm feeling, put me down and call me weak. But I guess they're just working through their own trauma when they say that. They don't realize that the life they've given me has allowed me to have the luxury, I guess, to address my own mental health and to have these conversations. To be more open with those around me and to break this generational cycle of self-neglect.

So my question for the next person is, do you ever feel guilty about disappointing your parents, for example, in terms of values, career, or lifestyle? And how do you reconcile having those feelings of guilt with your own acknowledged need for personal growth? Whether this be in terms of, you holding different values from your parents, you having a career that they don't want, or you having a lifestyle that they wouldn't have expected you to have, and they wouldn't want for you. And this can mean a lot of things. And so please feel free to interpret this question as you wish.

Initial Submission Date: 2021

Story 14

Story 15

L, Mixed, Tamil & German, 21, Stouffville

Do you ever feel guilty about disappointing your parents?

Play

4:45

AA

(00:00)